1.0: Chemistry Fundamentals

Although this course primarily covers biology, it is impossible to go through it without some knowledge of chemistry. The course spends most of its time covering the cellular level of an organism. At this small scale, we discuss individual molecules and their structure and function. Chemistry is needed to understand these molecules' dynamics.

Vocab List

- Atoms

- Molecules

- Isotopes

- Ions

- Valence Shell

- Valence

- Bonds

- Covalent bond

- Ionic bond

- Cations

- Anions

- Hydrogen bonds

- Van der Waals Forces

- Isomers

- Structural isomer

- Stereoisomers

- Cis-trans isomer

- Enantiomer

- pH and buffers

- Hydrogen ion

- Acids

- Bases

- Buffers

Written Explanation

Atoms:

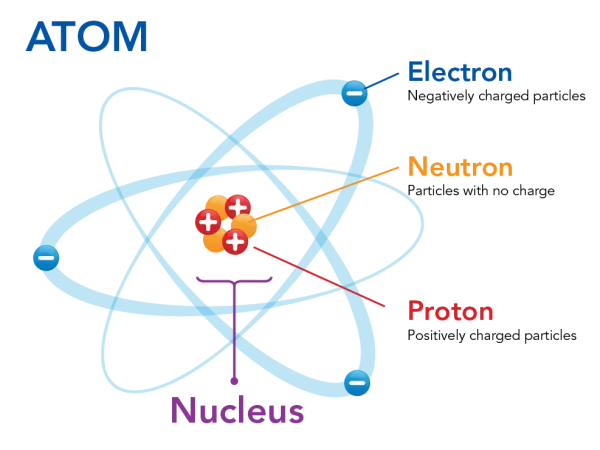

Atoms are the building blocks of the universe. Every object, every living organism, and everything else (even air) are made up of atoms and only atoms. However, atoms are also made up of other particles. These subatomic particles are called protons, neutrons, and electrons. Electrons have a negative charge, protons have a positive charge (proton = positive), and neutrons have no charge (neutron = neutral). Protons and neutrons are larger particles that are in the atom's nucleus, which makes the nucleus positively charged. The electrons orbit the nucleus (as negative attracts to positive), forming a sort of "cloud" around it. An element is all the atoms with the same amount of protons.

A diagram of a generic atom. NOTE: this model (and most others) do not accurately represent how electrons orbit the nucleus, but it is OK to think about it in this way

A diagram of a generic atom. NOTE: this model (and most others) do not accurately represent how electrons orbit the nucleus, but it is OK to think about it in this way

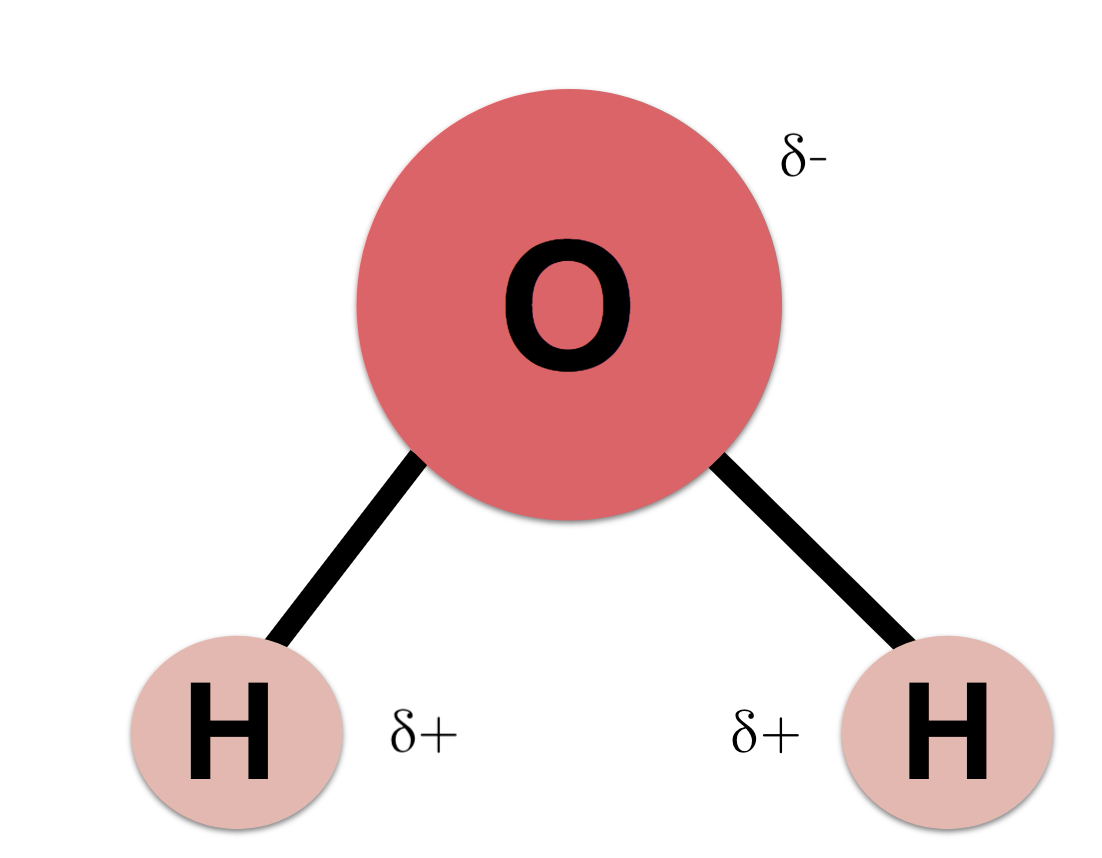

Molecules are groups of atoms that are bonded together (more on bonds later). A molecule's chemical formula is the list of the atoms that make it up and their quantities. For example, glucose's chemical formula is C6H12O6, meaning 6 carbon atoms, 12 hydrogen atoms, and 6 oxygen atoms.

A diagram of a water molecule, also known as H2O (2 hydrogen molecules and 1 oxygen molecule)

A diagram of a water molecule, also known as H2O (2 hydrogen molecules and 1 oxygen molecule)

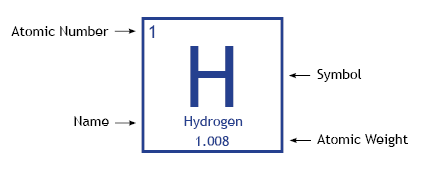

Every element on the periodic table is a unique atom, and is defined by the number of protons it has. As shown below, hydrogen has an atomic number of 1, meaning that it has 1 proton. It has an atomic weight of 1.008, which is the average weight of all of hydrogen's isotopes (described later). The atomic weight is usually the number of protons plus the number of neutrons in an atom.

A diagram showing the properties of a hydrogen atom

A diagram showing the properties of a hydrogen atom

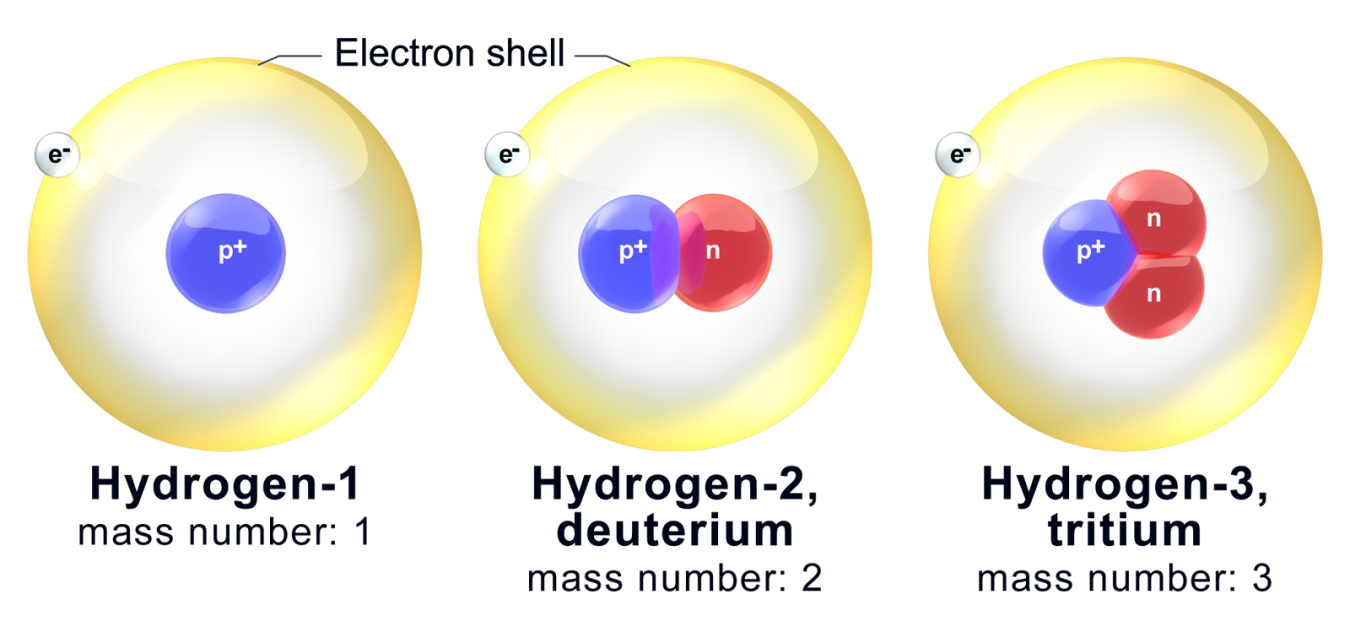

An isotope is an atom that has an abnormal amount of neutrons. Most atoms of a specific molecule have the same amount of neutrons, but isotopes of that element have a different amount of neutrons. For example, copper (atomic number 29) has two naturally occurring isotopes. One isotope is 63Cu (copper with atomic weight 63), which makes up 69.2% of copper. The other is 65Cu (copper with atomic weight 65), which makes up 30.9% of copper. Atomic weight is the sum of the weights of all the isotopes multiplied by their relative frequencies.

A diagram of the isotopes of Hydrogen: 1H (normal hydrogen), 2H, and 3H (used in nuclear reactors)

A diagram of the isotopes of Hydrogen: 1H (normal hydrogen), 2H, and 3H (used in nuclear reactors)

An ion is a molecule with an abnormal charge because it has an abnormal amount of electrons. Normally, the number of electrons equals the number of protons, but when they are unequal, there is an imbalance in charge. This is usually written as the element followed by the charge like so: H+, or Cl-.

The valence shell of an atom/element is the outermost layer of electrons orbiting the nucleus. As you can see in the diagram of gold below, two electrons will fill the innermost shell, 8 electrons fill the 2nd shell, and 8 in the 3rd.

A diagram showing the electron configuration of an argon (Ar) molecule

A diagram showing the electron configuration of an argon (Ar) molecule

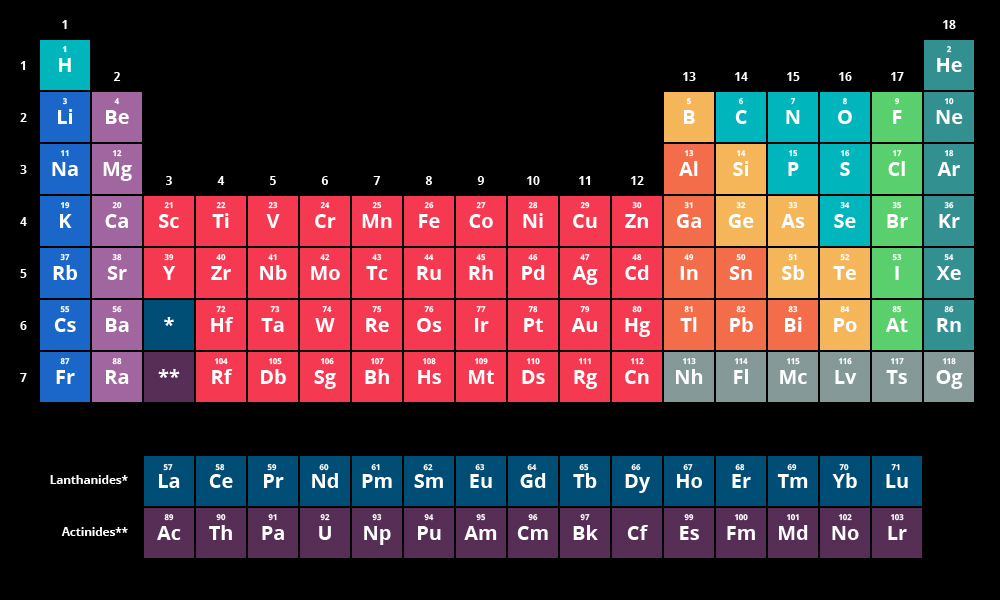

The valence of a molecule is how many bonds a molecule can make, which is based on how many electrons are in the atom's valence shell. The amount of electrons can be determined by looking at the element's position on the periodic table. The amount of electrons is (usually) the number of the element in its row. (Carbon is in the 4th position and has 4 electrons, Helium is in the 2nd position and has 2)

The periodic table of elements

The periodic table of elements

Bonds:

A chemical bond is a force that holds two atoms close to each other. This can be by the two atoms sharing an electron, or one atom giving up an electron to another atom. Atoms will bond because they "want" their valence shell to either be empty, or full (the valence shell being empty and full are the same things, just referring to different shells).

The first type of bonds are covalent bonds. Covalent bonds are formed when two atoms share an electron to fill both of their valence shells.

A diagram of a covalent bond between hydrogen and chlorine (HCl). Hydrogen's electron is shown by an X, and chlorine's by a circle. As you can see, hydrogen and chlorine are sharing an electron with each other to fill hydrogen's valence shell (up to 2) and chlorine's valence shell (up to 8)

A diagram of a covalent bond between hydrogen and chlorine (HCl). Hydrogen's electron is shown by an X, and chlorine's by a circle. As you can see, hydrogen and chlorine are sharing an electron with each other to fill hydrogen's valence shell (up to 2) and chlorine's valence shell (up to 8)

The second (and less common) type of bonds are ionic bonds. Ionic are formed when one atom "takes" an electron from another atom. The atom that lost its electron (and now has a positive charge) is called a cation, while the atom that gained an electron (and has a negative charge) is called an anion.

A diagram of an ionic bond between sodium and chlorine (NaCl). The sodium atom is giving an electron to the chlorine atom to satisfy both of their valence shells

A diagram of an ionic bond between sodium and chlorine (NaCl). The sodium atom is giving an electron to the chlorine atom to satisfy both of their valence shells

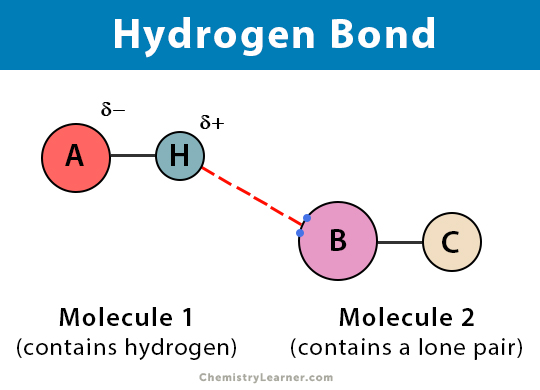

The last major type of bonds are hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bonds are the result of an attraction between slightly positive and slightly negative parts of molecules. For example, the surface of glass has a slightly negative charge, making it attract/bond to the parts of other molecules that are slightly positive (more on this in 1.1).

A diagram of a generic hydrogen bond

A diagram of a generic hydrogen bond

Lastly, Van der Waals Forces are small forces of attraction that exist between all molecules. They mostly take effect at short distances. Sometimes Van der Waals Forces are called hydrophobic interactions or London Dispersion Forces.

Isomers:

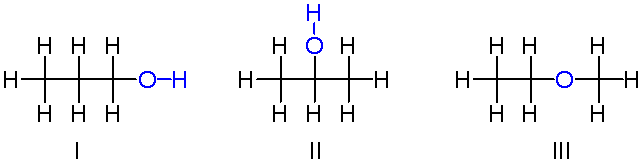

Isomers are molecules or compounds which share the same exact chemical formula, having the same number of atoms of each element, yet have differing arrangements of the atoms, resulting in a different structure. This means that the two molecules can fulfill different purposes or perform different functions, showing how a simple change not even the chemical makeup but just the arrangement of the bonds and atoms can lead to major changes overall. There are two major types of isomers, structural, where atoms are in different locations, and stereoisomer (or spatial) isomers, where even though the bonds are located in the same place, the spatial arrangement of the atoms differs.

An example of structural isomers: three molecules which have the same chemical formula, yet have oxygen and hydrogen atoms bonded in different places

An example of structural isomers: three molecules which have the same chemical formula, yet have oxygen and hydrogen atoms bonded in different places

Two kinds of stereoisomers are enantiomers, which are mirror image molecules, and cis-trans isomers, where two molecule groups double bound to each other are either rotated in the same direction (cis molecule) or in opposite directions (trans molecule).

Cis and trans isomers, where the chloride and hydrogen atoms double bound to the carbon are spatially rotated and appear as facing opposite directions

Cis and trans isomers, where the chloride and hydrogen atoms double bound to the carbon are spatially rotated and appear as facing opposite directions

pH:

Occasionally, a proton dissociates from, or leaves a molecule, resulting in only the electron being left behind. This can cause the formation of an ion. A proton can also be called a hydrogen ion, as hydrogen only contains one proton and one electron, and when it loses that electron it is just a proton. A water molecule (H2O) after the loss of a hydrogen ion becomes a hydroxide molecule (OH-), while a water molecule which gains a proton is known as a hydronium ion (H3O+). In pure water, only 1 in 554,000,000 hydrogen atoms in water molecules dissociate, which measured in moles (a value used to measure molecules) is 10-7 of a mole of hydrogen ions per mole of water.

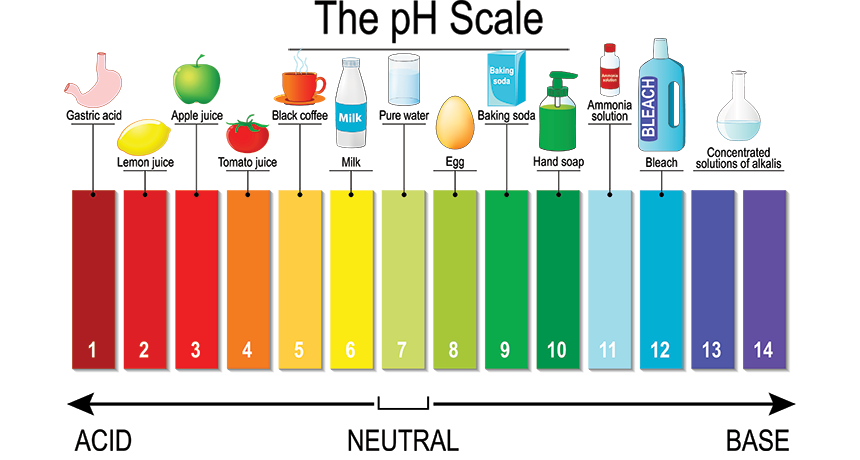

pH, or potential of hydrogen, is the measure of the dissociated hydrogen ion concentration within a substance. It can be found by taking the negative log of the hydrogen ion concentration (-log[H+]). Plugging in our value of 10-7, the pH of pure water is 7, which is also known as a neutral pH.

A diagram of the pH scale with examples at each level

A diagram of the pH scale with examples at each level

Acids are substances that have a low pH, meaning they have a high rate of dissociation of H+ ions (there is an inverse relationship between pH and amount of H+ ions). Acidic substances can give up hydrogen ions due to their excess.

Bases are substances that have a high pH, meaning they have a low rate of dissociation of H+ ions. They can accept hydrogen ions due to their lack of them. Sometimes basic substances are called alkali substances.

Lastly, buffers are substances that minimize the change in pH. They both accept and release H+ ions to maintain a balance in pH. Carbonic acid is a common buffer in your body.